The Quiet Ones

It’s the first day back for my kids.

My daughter is starting 8th grade at a new school, meaning our morning was predictably shouty and panic-filled, a flurry of loud activity right up until the second she left for the bus stop.

At home, with us, she’s almost never quiet about what she’s feeling. We get the best (and the less-than-fun parts) of her, and I’m grateful for both, that she’s comfortable enough to take her first-day nerves out on us before she wraps them tightly away for the school day; that she’ll dance in front of us, and sing, and be silly. She’s bursting and beautiful with personality, with life. With spirit.

She told me last year that a kid in her class was surprised, halfway through the year, when he heard her talk, and oh God, how that threw me back to my own school days, when I would have died rather than raise my hand to ask a question, when my more extroverted classmates seemed to take up all the air and so much space. I’m watching her figure out the things that I had to learn: how to navigate this world that seems built for, and which champions, those who talk more than they listen, those whose deeds are brash and bold rather than quietly courageous.

One of my first jobs out of college was as a reporter at a small regional insurance newspaper, which promptly laid me off a year later during the 2008 recession. Scrambling for work while, it seemed, half the country was doing the same, I took the first job I found—as a floating aide in a daycare center. I’d worked in daycares before, but never in one quite like this, where the chaos felt unrelenting and workers were expected to adhere to rigid schedules that left little room for connection with individual children.

The preschool classroom had unfortunate acoustics—a tall ceiling, huge, bare walls, a linoleum floor softened only here and there by thin rugs. Scattered about were a number of plastic tables and chairs sized for three year-olds, but no one was sitting in them; instead, the class’s fifteen or so kids were blurs of colorful motion, each and every one with their mouth wide open and shouting, seemingly just for the chaotic joy of making noise.

Each and every one—but one.

Miles had backed himself up against the wall by the door, out of range of any potential colliding bodies. He was a skinny kid with eyes that seemed too big for his face as he watched his classmates. The classroom teacher calmly ignored the general frenzy, counting out goldfish crackers into little paper cups for the kids’ snack, setting one in front of each chair at the miniature tables. As she turned away to grab more, three little boys leapt up onto one of the tables, bashing at each other with pool noodle swords, upsetting the cups, from which goldfish leaped like escapees from a fisherman’s bucket, only to be crushed to crumbs under small stampeding feet. The noise reverberated around the room, amplified by so many hard surfaces.

Miles had by now pressed himself so firmly against the wall, it looked like he was hoping the wall would swallow him.

The preschool classroom was my least favorite place to which I had to “float,” mostly because I was forced to look on as little Miles shrank into himself a bit more each day. On rainy days, as the other kids zoomed around the gym on tricycles or flung balls at one another and against the walls, shrieking all the while, Miles found the only chair in the room and sat down on it, shoulders hunched as balls flew over and around him, watching.

“He’s not like this at home,” his mother told me once, and now that I have kids of my own I know, intimately, the desperation I heard then in her voice: Please, let others value my child as he is. Please, just let my child be happy. “He’s boisterous. He loves to play!”

Once, I knelt next to Miles’s chair.

“It’s loud in here, isn’t it?” I said, and he nodded, shoulders hunching further. I offered him my hand and asked if he wanted to stand by me, or maybe play catch together by the wall—and then the head teacher pulled me away, shaking her head.

“You must let him play with the other children!” she said. “He’s so small and quiet, but he’ll never learn to run with the others if we interfere.” Then she crossed her arms and jerked her chin in the little boy’s direction, saying to me in an undertone, “I do wonder if he can play, sometimes. That one just has no spirit.”

More than a decade later, I would include her words, just slightly altered, in my second novel.

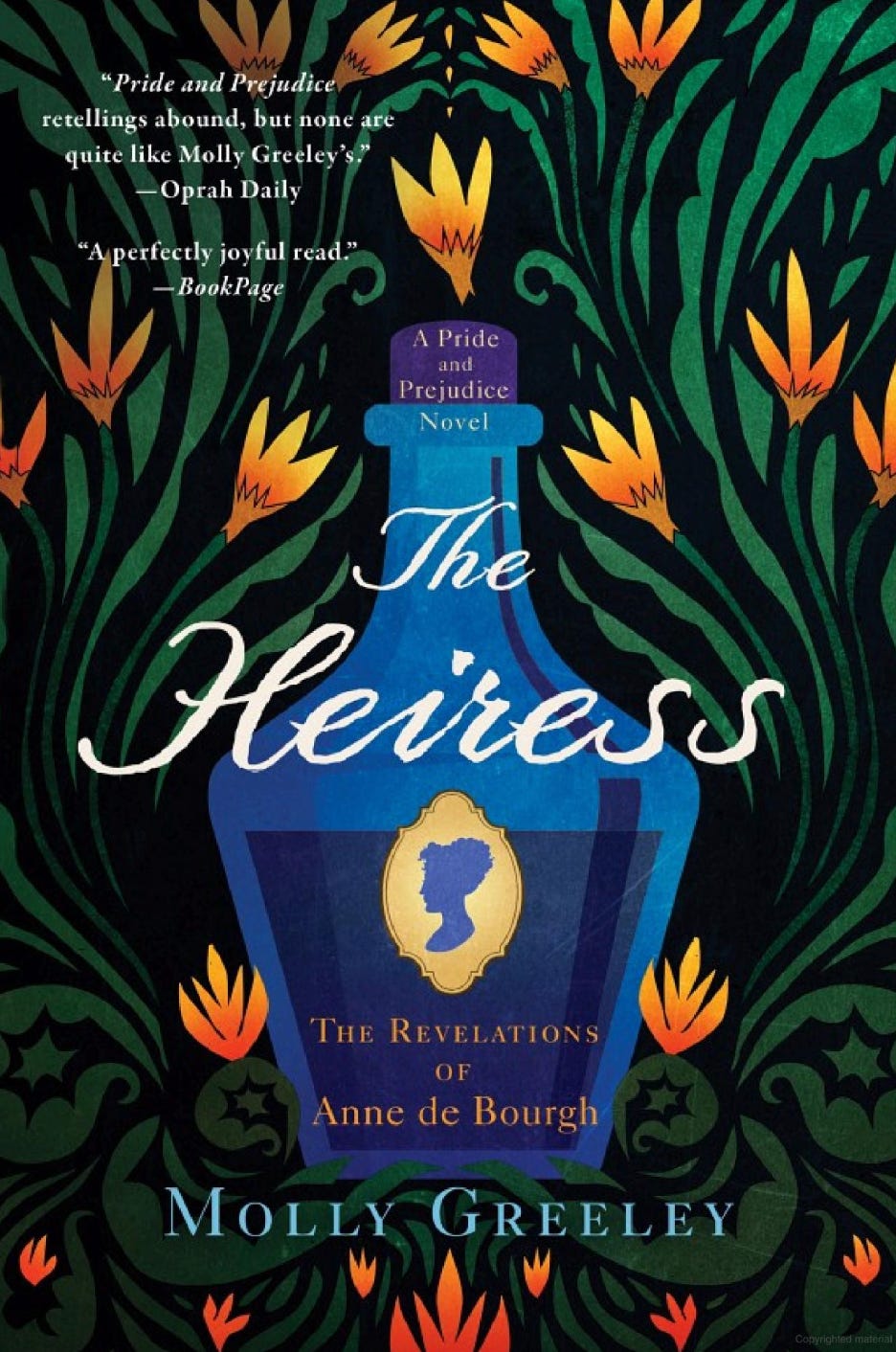

When I began my second novel, it was not with the intention of writing an introverted protagonist (though that was, it turned out, what I did). The Heiress is the story of Pride and Prejudice’s Anne de Bourgh, a young woman of vast fortune and seemingly not much else. In Jane Austen’s novel, she is a listless, spiritless invalid, scorned by Elizabeth Bennet, the book’s very spirited protagonist; in The Heiress, I set out to explain her apparent illness, and to give her both an inner and, eventually, outer life.

But when she is a child, she is still sickly and small, with an active imagination, a quiet body. During a visit from her aunt—whose son is the infamous Mr. Darcy, Elizabeth Bennet’s eventual love interest in Austen’s original—Mrs. Darcy is appalled by Anne’s quietness, and it is from her mouth that the daycare teacher’s words emerged as I typed:

“She is just so—small. And so quiet.” Aunt Darcy lowered her voice still further.

“She seems to have no spirit at all.”

Anne, in my novel, is a dreamy sort, given to introspection, but she is also capable of practicality, of seeing injustice in the world and doing doing what she can to rectify it, drawing on deep reserves of inner strength. Yet even when she does so, it is quietly.

I was beyond grateful to receive lovely reviews from such well-known outlets as Oprah and Booklist. But the two responses below, which recognized Anne’s strength even in her quietness, felt especially meaningful to me. One reviewer wrote that Anne's journey was “haunting and inspiring in a quiet and meditative way,” and a reminder that “there are many ways to be kick-ass.” And a reader shared that seeing “a true introvert reflected on published pages” was deeply satisfying—and called Anne their “favorite heroine” in a long time.

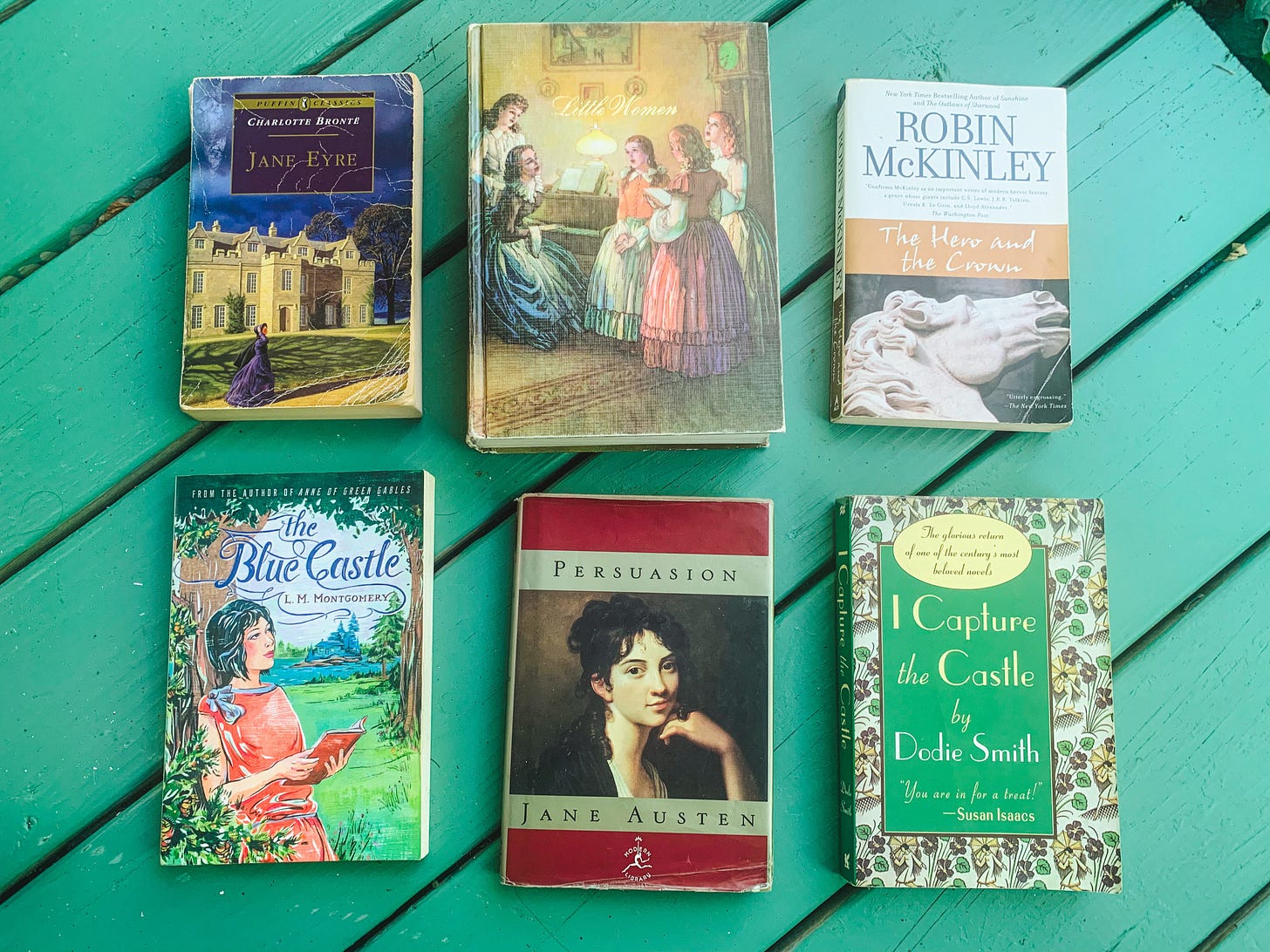

I suppose it should be no surprise that looking back at some of my favorite books from when I was around my daughter’s age, many of them feature heroines who are watchers, listeners. Helpers, but not in ways that get them big recognition. Think Beth March in Little Women, Aerin in The Hero and the Crown (really, the hero or heroine in almost any Robin Mckinley book), Cassandra in I Capture the Castle, Anne Elliot in Persuasion, Valancy in The Blue Castle. Jane Eyre! These characters’ journeys were often as much internal as external; they lived life according to their principles, regardless of whether others thought them odd, even sometimes committed classically heroic acts (Aerin literally slays dragons, but, somehow, quietly).

Today, I’m wishing my daughter, and all the quiet kids, a school year in which they find their people—those who see them as kick-ass whether they’re slaying dragons or speaking up in class even when it’s scary, and who know that spirit is as much about what’s happening inside as what we see from the outside.

What I’ve recently read and loved:

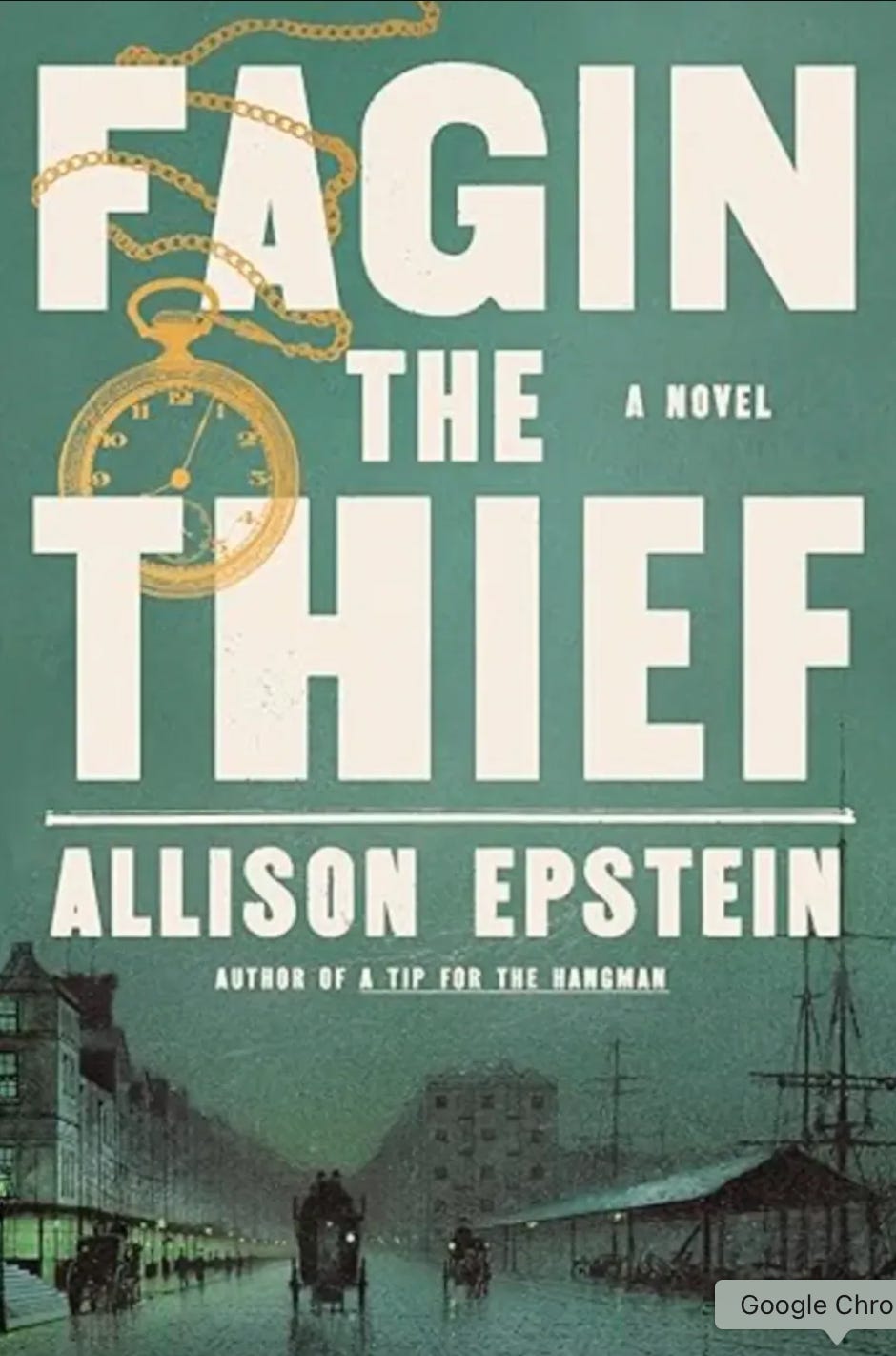

I very much enjoyed both of Allison Epstein’s previous historical novels, so when I heard that a third was in the works—an Oliver Twist retelling from the POV of the villainous Fagin—I was all anticipation. When I got my hands on a copy of Fagin the Thief, though, I found myself blown away—Epstein’s usual nuanced characters, immersive settings, and beautiful prose are fully in evidence here, but heightened. Readers will live in Victorian London; they will feel Fagin’s heart pounding inside their own chests as he approaches his first theft.

And they will feel for these characters—not just Fagin himself, whose backstory goes a long way toward rendering him sympathetic even as he sticks firmly to the morally-gray shadows, but for every character who breathes in these pages. Even the housebreaker Bill Sikes is a fully realized human being here, someone I could understand and feel for deeply even as I loathed so many of his actions—which anyone familiar with the original story will realize is a fantastic feat on Epstein’s part.

This book is masterful—historical fiction at its best.

(Also, Allison has a hilariously funny Substack account! You must follow Dirtbags Through the Ages if you enjoy irreverent history.)

Welcome to Substack! Looking forward to your posts! 💕